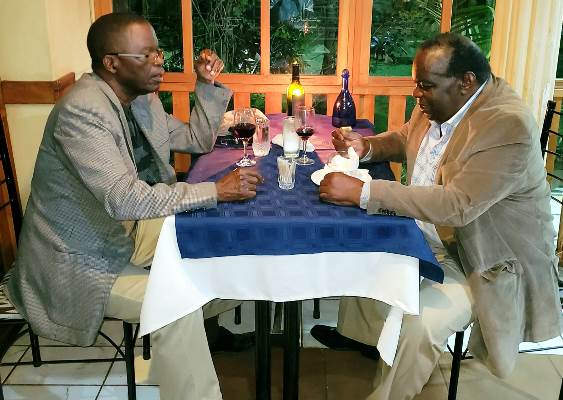

Every time I traveled to Lilongwe I made an effort to meet Goodall. He faulted me whenever I didn’t. Red wine at his house. A lunch or dinner outing, at Four Seasons or some other place. Endless conversation, candid opinions. An abundance of mischievous jokes at each other’s expense.

Goodall was a master of wit and self-effacing humour. He knew I enjoyed the banter, and he kept repeating his stories every time we met. “Let me tell you this one about a certain Phoka gentleman in the 1950s,” he would start.

I was, of course, always mindful that Goodall was the towering giant, and I the midget, grateful to be in his company. Some people find it difficult to mix with lesser mortals. Not so with Goodall. Like all trully great people, he opened up to you to the point that you began to feel he was your equal. We developed a degree of camaraderie. He would rip me to pieces and get away with it; and I would return the favour without negative consequences.

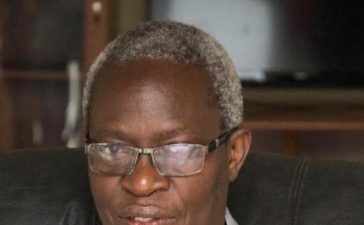

Goodall’s remarkable accomplishments as an economist, internationally and here at home, have earned him universal acclaim. But he was also a man with a greatly refined liberal sensibility. He had a deep interest in the arts, was well-read in the humanities, and I can attest to his flair for the occasional Shakespearean allusion. He once changed the time of my London rendezvous with him in order to attend a classical concert at the Royal Albert Hall featuring his favourite composer.

On a visit to his Mzimba village, I found that people held him in great awe. In the Tumbuka language certain words are uttered in a way that expresses nuanced feelings particularly well. In Goodall’s village I heard the salutation “aDada” pronounced with an intonation that combined love with deep respect in a way that conveyed Goodall’s patriarchal position in the community.

But that was more than matched by what I saw when Goodall and I strolled from desk to desk during a mission to the IMF offices in Washington. The respect for my senior colleague, among IMF officials young and old and of all races, many of whom had pretty much been trained on the job by him, verged on near-worship. On later visits without him, when negotiations hit difficult patches, I sometimes felt tempted to say “hey folks, don’t forget I’m the one that came here with Goodall the other day,” just to get some respectful attention. Alas, greatness does not so easily rub onto others.

Last week I travelled to Lilongwe again. I knew Goodall was unwell and I wanted so much to see him. So very much. When I called, it was his wife Gertrude who answered the phone. Sadly, there were understandable difficulties, and on the fourth day I had to accept that I couldn’t see my bed-ridden friend. That was not easy.

But then on Sunday, as I drove back to Blantyre, Goodall called me. I stopped by the roadside, and we spoke for a few minutes in what turned out to be our last conversation.

Very few people go into politics and come out without being tainted in some way. But with Goodall the consensus among Malawians is that he was eminently competent, patriotic, honest, humble, well-meaning and a force for good. These are qualities that have now sadly become scarce commodities, scarcer even more than fuel.

Oh friends, oh countrymen, though I be no Marc Anthony, do kindly lend me your ears, for I come to praise Goodall, not to bury him. The good that men do is indeed often buried with their bones, but that should surely not be the case with this extraordinary citizen?

Pepani Gertrude. Pepani family. Nkhuzi ya pa Enukweni, nkhuzi pakati pa zinyakhe, yaruta. May his soul rest in peace.

Goodall Edward Gondwe 1936-2023