Perhaps unbeknown to some is what landlocked status means for a country. As for Malawi, the effect on the economy is huge. While trade and transport costs are high in Africa, in Malawi they are among the highest in region therefore making imports and exports expensive because of time-consuming and poor-quality rail and road transport. While the average cost is approximately $7 per ton, per Kilometer, in Malawi it costs $7-$10. UN Economic Report on Africa reveals that Malawi’s transport sector accounts for 56 percent of landed transport costs and 30 percent of export costs, thereby increasing the costs of imported consumer goods by 15 percent and hurting Malawi’s regional trade competitiveness.

Proximity to the sea and discovery of routes that shorten the distance have been identified as a panacea to these expenses. Therefore, solicitation of solutions to shorten the distance to the sea and curb transport expenses have dominated Malawi foreign policy since 1964. The foreign policy issue comes into the equation mainly because Malawi relies on four main external trade corridors: the ports of Dar es Salaam in Tanzania; Beira and Nacala in Mozambique and Durban in South Africa. Good relations with these countries, therefore, become key.

The main line of the rail system in Malawi consists of a network of railways running from Salima to Nsanje, a distance of 439 km and is operated by Malawi Railways. Inaugurated by Malawi’s founding President, Hastings Kamuzu Banda, the line was extended from Salima to Lilongwe in 1977 and was later extended to Mchinji, on the border with Zambia. At Chipoka, 32 km south of Salima, the railway connects with the Lake Malawi steamer service, also operated by Malawi Railways. The railway line extends, in the south, from Nsanje to the port of Beira in Mozambique. The Central African Railway Cmpany, a subsidiary of Malawi Railways, operates the 26 km span from Nsanje to the Mozambique border. In 2017, 145 km of rail path was constructed bringing the accumulated railway length to 942 km.

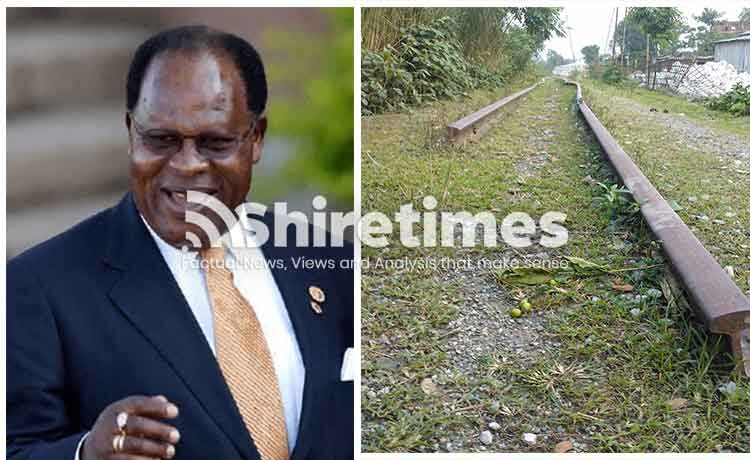

Although the railway network may still be in existence, most part of it is completely obsolete and the entirety of it is in old fashion. The misfortune that brought the rail transport to its death occurred between 1994 and 1999. It appears that the rise of Bakili Muluzi and UDF to the country’s leadership was the beginning of Malawi’s economic downfall.

Muluzi’s reign came like a plague ransacking everything that was good, the railway transport system was never spared. At the pace Malawi took rail transport seriously to the heart of its economy, it remains reasonable imagination that perhaps by now Malawi would be having intercity bullet train for human transport. While the railway transport was thriving with more railways being constructed throughout the 30-year rule of Kamuzu Banda, barely within 5 years of Muluzi’s regime rail transport declined and with a zero effort to maintain, upgrade or construct extra ones. The final nail to the coffin of the industry came through privatization in 1999 which was wrongly perceived to solve problems in the parastatals. Muluzi and his allies in the logistics industry pedaled the move to deliberately destroy the railway industry to favor their tanker businesses.

While Muluzi was visibly clueless on the importance of the rail transport to Malawi’s economy, Bingu came into the scene with a promising vision. The Nsanje World Inland Port came into the picture. For Bingu, the construction of an inland port at Nsanje meant linking land-locked Malawi with the Indian Ocean port of Chinde, 238 kilometers away in neighbouring Mozambique, through the Shire-Zambezi Waterway project. The aim was to reduce the high costs of importing and exporting goods by road via Malawi’s commercial capital, Blantyre, and the Mozambican port city of Beria – a round trip of about 1,200 kilometers.

But Mutharika’s enthusiasm for the project was not matched by his counterpart in Mozambique. As Mutharika presided over the official opening of the port in October 2010, flanked by former Zambian president Rupiah Banda and Zimbabwean president Robert Mugabe, he had to admit to the crowd gathered to witness the arrival of the first barge that the Mozambican government had called for environmental and feasibility studies before it would allow any barges to navigate the Zambezi River portion of the waterway, which flows through its territory.

While it is proven that the route offers the shortest distance from Blantyre to the sea, Bingu failed to bargain a buy-in from the Mozambican government. Since then, the port has sat idle, gradually shedding nuts and bolts to vandals and becoming the focus of increasing resentment from local people who were promised jobs and development. We can admit, however, that the only improvement that the project brought to Nsanje has been the paving of a 50-km stretch of road linking Nsanje with Bangula, the next town. Much of the remaining 130km of road between Nsanje and Blantyre has yet to be tarred.

Nonetheless, an assessment by SADC revealed that though the project was technically feasible, it was rather not financially feasible as it would offer limited capacity to transport goods and was estimated to cost the country approximately $80 Million a year for maintenance. This encouraged the Mozambican government to withdraw their interest in the project. Beyond that, the project posed an economic risk to Mozambique as it would lose out on toll and freight charges for foreign vehicles that use its transport network.

Later on, Peter Mutharika through the DPP manifesto of 2014 promised to resuscitate the project once elected President. In 2014, he got to the Presidential seat following a presidential election and became a stranger to his own promise. He kept on peddling lies about signing an agreement with Mozambican government to proceed with the project but nothing came to fruition.

However, President Lazarus Chakwera was bold enough to abandon the Shire-Zambezi inland port assuring the nation it does not offer the best comparative option to railway transport. The focus for the Chakwera administration in the matters of opening the country to the sea is through the rehabilitation of the railway line to Beira in Mozambique through Nsanje. In October 2020, President Chakwera held bilateral talks with President Felipe Nyusi of Mozambique to embark on construction projects to connect Malawi to Beira through Nsanje, just as it was in Kamuzu era. Since then construction is underway and is expected to yield dividends on Malawi’s economy.

Using estimations for Kachaso-Nkaya railway stretch on a 145KM distance which indicate generation of about $50 Million per year and creation of 2,000 jobs along the line, the Beira network will proportionately generate $33 Million per year and create 1,350 jobs. On a bigger picture, this will increase exports by about 200,000 tonnes per year. One can only imagine how much revenue the government will collect through concession fees, how many jobs it will create and how much expenses will be cut back from transportation if all the dormant railways will be rehabilitated. Obviously as this happens the price of goods will locally fall as import costs will be lower. Foreign trade for Malawi’s exports will increase as competitiveness will be feasibly secured through reduced export costs. That is Chakwera’s vision seeking to resuscitate rail transport to boost the economy. Bravo!

Written By: Precious Kankuzi (MSc.) & Fanuel Lindani

Edited By: Innocent Marshall

If you have any content that you would like to share with us for publishing, kindly send us an email: editor@shiretimes.com