Politics often rewards energy, loyalty and courage. But it just as ruthlessly punishes impatience, excess and loose talk. Few recent stories illustrate this brutal truth better than the rapid rise—and equally rapid deflation—of Alfred Gangata, once touted as one of the most powerful young figures in the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP).

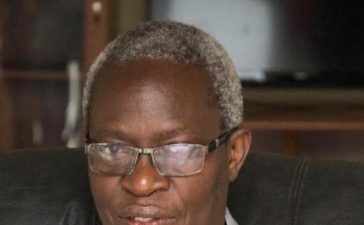

Gangata is young, ambitious and undeniably hardworking. He invested time and effort mobilizing for the DPP in the Central Region, an area traditionally hostile to the party. That courage did not go unnoticed. President Peter Mutharika rewarded him with a powerful and highly symbolic post: Minister of State in the Office of the President and Cabinet.

The office was not sold to the public as just another ministry. Mutharika himself framed it as a command post above the rest—an all-seeing, all-coordinating position. Gangata, Malawians were told, would operate directly from the President’s office, overseeing ministers, intervening across portfolios and reporting only to the Head of State. In effect, he was presented as first among equals in Cabinet.

It was a heady elevation. Too heady, perhaps.

Barely settled into office, Gangata appeared to internalize the myth of invincibility. Allegations of abuse of power began to swirl, with his private security firm, Masters Security, reportedly scooping lucrative government contracts worth billions of kwacha—from Malawi Revenue Authority tenders to CEAR-related deals. The optics were terrible. The message was worse: that public office had become a conveyor belt for private enrichment.

This did not escape the attention of the true power brokers within the DPP—the party’s entrenched elite, its financiers and regional custodians. To them, Gangata’s growing wealth, expanding influence and open bravado rang alarm bells. Matters were not helped by his own public statements. In one interview, he openly admitted that he was not an “honest businessman,” aligning himself with what he described as a group of “crooked” entrepreneurs who bend rules to build empires. In another moment of candor—or recklessness—he spoke of future leadership ambitions within the party, even floating 2030 as his target.

That, effectively, sealed his fate.

The DPP is not a political playground. It is a tightly guarded enterprise, deeply rooted in regional power structures, particularly the Lomwe belt. Leadership succession is not improvised, nor is it entrusted to rising stars who show signs of independence, wealth and ambition beyond the control of the party’s inner circle. Gangata’s trajectory suggested not loyalty, but a future headache—a man whose money and influence could turn succession battles into political warfare.

The response was swift, cold and calculated.

Less than six months after his appointment, the axe fell. A cabinet reshuffle dissolved the Ministry of State altogether—an unmistakable signal that the office had been created for a person, and destroyed because of that same person. Gangata was demoted from near the top of Cabinet hierarchy to a much lower rank, reassigned to the Ministry of Natural Resources.

The symbolism could not be louder. From the President’s inner sanctum to forests, wildlife and charcoal. From political overseer to resource custodian. It was not just a reshuffle; it was a rebuke.

Gangata’s story is also one of unpolished instincts. He is bold, but politically raw. He speaks when silence would serve him better. He reveals his ambitions instead of disguising them. He boasts where seasoned politicians scheme quietly. And hovering over all this are unresolved personal controversies that weaken his moral standing and credibility.

In the ruthless arithmetic of power, this makes him expendable.

It would not surprise this paper if Gangata’s demotion is merely the beginning. Future reshuffles may remove him altogether. Post-election, he offers little strategic value to a party focused on consolidation and control. And with bridges burned elsewhere, his political options are narrowing fast.

This is a familiar tragedy in Malawi’s politics: young, energetic figures elevated for tactical reasons, used for electoral gain, then discarded when they grow too visible or too ambitious. Unless Gangata recalibrates—embracing discipline, discretion and wiser counsel—his political career risks becoming another cautionary tale.

Ambition is not a crime. But in politics, ambition without patience is often a death sentence.