This is not a courtroom drama. It is a battlefield. And the smoke is rising from Malawi’s judiciary.

Anti-corruption lawyer Alexious Silombera Kammangira has declared open war. From Ireland, where he is pursuing further studies, he addressed Malawians on Facebook—not with whispers, not with diplomacy—but with artillery fire. His target: what he describes as a judiciary rotting from within.

The spark? A controversial Supreme Court decision awarding Finance Bank damages for loss of profits dating back to 2005. For many citizens, it was not just a judgment. It was a financial grenade lobbed into the public interest. For Kammangira, it was confirmation of something darker.

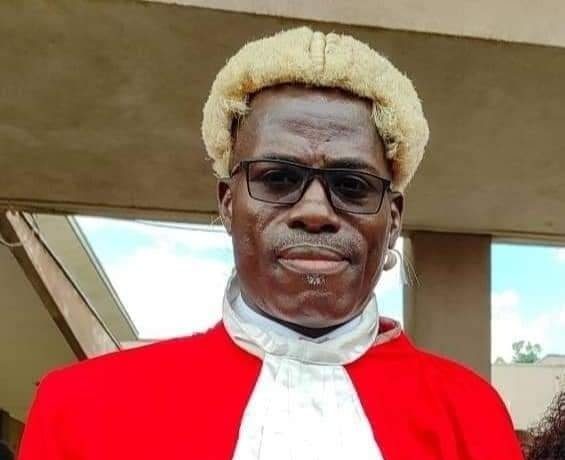

At the center of his accusations stands Lovemore Chikopa—whom he brands the “undisputed prince of corruption” within the judiciary. Not incompetence. Not error. Corruption. Calculated. Systematic. Profitable.

Kammangira alleges a pattern: every case involving serious money allegedly funnels through Chikopa. The machinery, he claims, runs with the assistance of Frank Mbeta, now Attorney General. According to him, Mbeta is not a bystander. He is an operator.

The mechanics, as laid bare by the activist, are crude and transactional. In the Salima Water Project case, he alleges that lawyer Bright Theu—appearing pro bono for the Malawi Law Society—was approached by Mbeta and told to “call your figure” to secure a favorable ruling for his client. Theu himself later wrote about the encounter publicly. If that account stands, this was not legal persuasion. It was price-tag justice. Not argument. Not merit. An auction.

Kammangira’s logic is ruthless: if the gatekeepers are compromised, the fortress falls. He argues that fighting corruption while Mbeta sits as Attorney General is structurally impossible. In his words, Mbeta is embedded in “every transaction stinking corruption.” Shielded, he claims, by Chikopa.

One explosive allegation: Chikopa allegedly issued an order preventing the Anti-Corruption Bureau from investigating Mbeta in a tax-related matter involving the Malawi Revenue Authority. Another: Mbeta allegedly acted as a conduit for funds intended to influence judges during the 2020 election case. These are not minor infractions if true. They are systemic sabotage.

Kammangira also questioned why former President Peter Mutharika appointed Mbeta as Attorney General, calling it a lost opportunity to clean house. He widened the blast radius, naming other lawyers—including Wapona Kita—as part of what he describes as a collusive network between certain legal practitioners and judges to siphon public resources.

This is not Kammangira’s first assault. He previously targeted commercial judge Ken Manda, accusing him of issuing rulings dripping with the hallmarks of corruption. Manda was subsequently sent on leave pending further action.

The story unfolding is stark. Either these allegations are reckless and false—or they expose a judiciary compromised at its highest levels. There is no comfortable middle ground.

In war, clarity matters. If the claims are baseless, they demand firm rebuttal backed by transparent evidence. If they carry weight, then Malawi is not facing isolated misconduct but an institutional crisis.

A judiciary survives on one currency: trust. Once that collapses, the robes mean nothing. The gavel becomes theater. And justice becomes merchandise.

Malawi now stands at a fork in the road. Investigate thoroughly and transparently—or allow suspicion to metastasize. Silence will not save the institution. Only truth will.