The letter from Lilongwe Girls Secondary School is not just an administrative notice. It is a policy red flag.

Government promised free secondary education. It won political capital on that promise. Yet what parents are now receiving is a confusing arithmetic of deductions, exceptions, and half-clarifications that quietly redefine “free” into something else entirely.

First, the sequence matters. Government announced that from April, all secondary education—including boarding—would be free. That was clear, bold, and politically consequential. Later, after engagements with church-owned and government-aided schools, the promise was diluted: development fees removed, boarding fees retained. Now Lilongwe Girls—a fully government-owned boarding school—appears to be applying a similar formula. Not free boarding, just a revised boarding fee.

This is where policy coherence collapses.

If church-owned schools are allowed to charge boarding fees while government-owned schools are supposedly free, what exactly is the policy baseline? Are learners in church-owned schools expected to eat better, worse, or differently? Are government schools being asked to lower meal standards to fit a “free” model? If standards differ, then the policy quietly sanctions inequality. If standards are the same, then someone is absorbing costs without clarity—or without honesty.

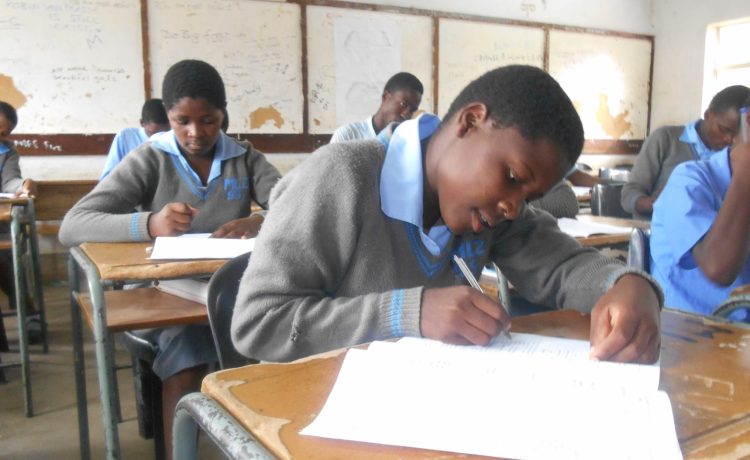

We have already seen the consequences of poor diet planning: strikes, vandalism, and unrest in the first term. Food is not a footnote in boarding schools; it is the spine of discipline and stability. A “free” policy that forces schools to stretch thin budgets without explicit safeguards is not progressive—it is combustible.

The core question remains unanswered: Is secondary education free in full, or free in parts?

Partial freedom dressed up as total reform is worse than no reform at all. It breeds mistrust, confuses parents, overburdens school administrators, and radicalises students who feel shortchanged. Policies do not fail only because they are bad; they fail because they are vague.

The DPP government owes the country clarity, not circular memos. Spell it out: what is paid, what is not, who pays, and who absorbs the cost. One policy. One standard. One message.

Education reform should not be an exercise in fine print. If this ambiguity persists, the promise of free secondary education will not uplift Malawi—it will destabilise it.