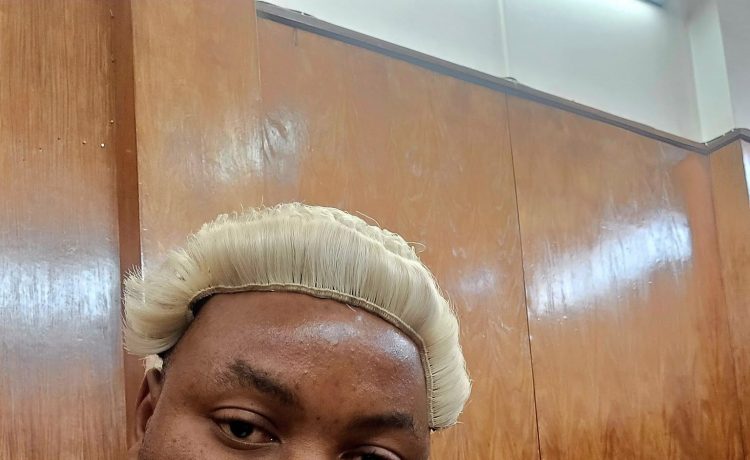

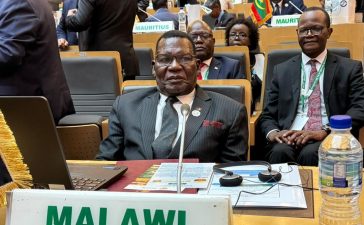

In a heartfelt reflection that has struck a chord across social media, one of Malawi’s most outspoken legal minds, Khumbo Soko, has delivered an impassioned tribute to Malawi’s democratic resilience—praising the country’s political maturity in a region increasingly marred by repression, fear, and state-sponsored violence.

“Kunoko ku Malaŵi kuno tidziwelenga madalitso athu. Ndipo tidziatcula limodzi limodzi,” Soko wrote—loosely translated as ‘Here in Malawi, we must count our blessings, one by one.’

In his characteristically candid tone, the prominent lawyer drew sharp contrasts between Malawi’s democratic conduct and the grim realities unfolding elsewhere on the continent.

“When you see what happens in most countries in Africa—Uganda, Zimbabwe, Tanzania—it makes you realize just how far we’ve come,” he wrote. “In Uganda, for instance, the opposition doesn’t just run against the ruling party. They run against the police and the military, who go out of their way to frustrate any meaningful campaign.”

Soko noted that Malawi’s democratic record—marked by four peaceful transitions of power since the return to multiparty rule in 1994—remains a beacon of hope in a region where dissent is often crushed and elections rigged.

“Here, on four occasions now, we’ve had the party in power lose power, and while not perfect, the transfer of power has proceeded largely peacefully,” Soko observed. “Our police, though sometimes partial, generally allow the opposition to campaign. Our military has stayed true to its constitutional duty.”

He praised the Malawi Electoral Commission (MEC) for conducting “reasonably transparent and competent” elections and noted with pride that the country has yet to experience internet blackouts or digital censorship during polls—an increasingly common authoritarian tactic elsewhere in Africa.

Soko, who has often been a vocal critic of government excesses, appeared deeply reflective this time—urging Malawians to acknowledge their democratic progress even as they continue demanding better governance.

“Our courts aren’t perfect—no institution is—but one can still go there, present grievances, and expect a fair hearing,” he wrote. “While we have a long way to go, we are better, in fact much better than most places where democracy is in decline. But as is often the case, familiarity breeds contempt.”

In a poignant close, Soko expressed pride in his Malawian identity, adding with a touch of humor:

“I didn’t choose my association with this small country. But there are a lot of things about us that make me extremely proud to belong. Today, I just wanted to appreciate my homeland. PS: where can I buy the national flag, by the way?”

In a continent where lawyers and activists are often silenced for lesser words, Soko’s message stood out—not only for its candor, but for its rare optimism.

It was a reminder that amid the imperfections, Malawi’s democracy—hard-won and fragile—remains alive, resilient, and worth defending.